check

check

check

check

check

check

check

check

check

check

In the world of industrial automation and machine safety, the precise detection of objects is paramount. Among the various sensing technologies, the proximity sensor stands out for its reliability and non-contact operation. A specific configuration, the normally closed (NC) proximity sensor, plays a critical role in countless safety and control circuits. Unlike its normally open (NO) counterpart, a normally closed proximity sensor is designed to complete an electrical circuit in its default, non-activated state. When a target object enters the sensor's detection field, the internal switch opens, breaking the circuit. This fundamental behavior makes it an indispensable component for fail-safe designs.

The principle of operation for an inductive normally closed proximity sensor, commonly used for metal detection, is based on electromagnetic fields. The sensor generates an oscillating electromagnetic field from its face. In its resting state with no target present, this field remains stable, and the output switch is closed, allowing current to flow. When a ferrous or non-ferrous metal target enters this field, it causes eddy currents to form on the target's surface. This dampens or loads the oscillator's amplitude, which is detected by the sensor's circuitry. This detection triggers the solid-state switch to change state—opening the circuit and stopping the current flow. For capacitive NC sensors, used for non-metallic materials, the change in capacitance when a target approaches triggers the same switching action.

The choice of a normally closed configuration is often driven by safety and logic requirements. In safety-critical applications, the fail-safe principle is a cornerstone. A normally closed sensor is inherently fail-safe for monitoring run-off or breakage scenarios. For instance, consider a protective guard door on a machine. A normally closed proximity sensor can be installed so that when the door is properly closed, the sensor is activated (target present), and its switch opens. The control system interprets an open circuit as "door safe." If the door is opened, the target moves away, the sensor reverts to its default closed state, completing a circuit that signals an immediate machine stop. This ensures that any wire breakage or power loss to the sensor itself will also result in a closed circuit, triggering a fault or stop condition, thereby enhancing safety.

Another significant application is in routine process monitoring where the normal state of a system is "active." A classic example is monitoring the rotation of a shaft or the presence of a product on a conveyor. A normally closed sensor can be positioned to detect a tab on a rotating shaft. When the tab is present (machine running), the sensor's switch is open. If the rotation stops and the tab remains in place, the circuit remains open, but a timing circuit can detect the lack of switching. More importantly, if the tab moves out of position or falls off, the sensor switch closes, sending an immediate fault signal. This logic often simplifies PLC programming, as a "true" or "1" signal can directly represent a fault condition without the need for inversion instructions.

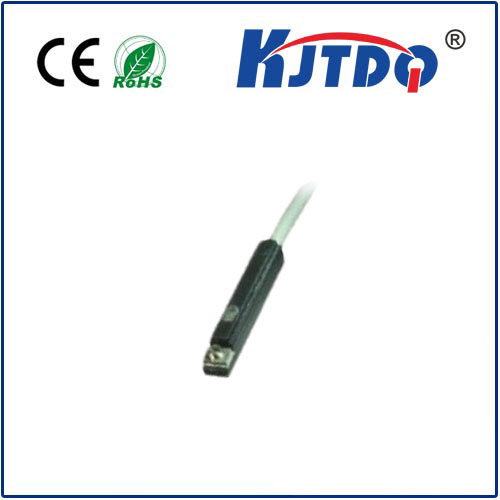

When integrating a normally closed proximity sensor into a system, several key specifications must be considered alongside the switching logic. The sensing distance, or rated operating distance, must be chosen with a safety margin to account for target variations and mechanical tolerances. The housing material, typically nickel-plated brass or stainless steel, must withstand the industrial environment. Electrical characteristics are vital: the output type (typically PNP or NPN for DC sensors), voltage range, and current-carrying capacity must match the load. The connection method, whether 2-wire, 3-wire, or 4-wire, also impacts the wiring and compatibility with controllers. It is crucial to consult the manufacturer's datasheet to understand the exact behavior, as some sensors offer configurable NO/NC outputs via wiring or programming.

Troubleshooting a normally closed circuit requires a shift in mindset compared to normally open systems. Using a multimeter, a healthy, unactivated NC sensor (with no target present) should show continuity or low resistance across its output wires. When a target is brought into range, this continuity should break, showing high resistance or open circuit. A common point of confusion arises during bench testing; a sensor that appears "always on" might actually be functioning correctly in its NC mode. Understanding the intended logic of the application is essential for correct diagnosis. Regular maintenance should include checking for physical damage, buildup of debris on the sensing face, and ensuring the target is within the specified sensing range and material compatibility.

In conclusion, the normally closed proximity sensor is not merely an alternative but a deliberate design choice for enhancing system safety, reliability, and logical clarity. Its default closed-circuit state provides a robust method for implementing fail-safe conditions, making it a preferred solution for machine guarding, rotational monitoring, and any application where a broken wire should trigger an alarm rather than go unnoticed. By understanding its operational principles, key specifications, and application logic, engineers and technicians can effectively deploy these sensors to create more secure and dependable automated systems. Selecting the right sensor configuration—NO or NC—is fundamental to designing control circuits that behave predictably under both normal and fault conditions.