check

check

check

check

check

check

check

check

check

check

In the intricate world of modern engineering and process management, the concept of limit control stands as a fundamental pillar of safety, efficiency, and reliability. This mechanism, often operating silently in the background, is the unsung hero that prevents systems from exceeding their designed operational boundaries, thereby averting potential failures, accidents, and costly downtime. At its core, limit control is a form of automated regulation designed to enforce predefined thresholds. These thresholds can pertain to a vast array of parameters: temperature, pressure, speed, flow rate, voltage, or even logical states within a software application. The primary function is to monitor a specific variable continuously and, upon detecting that it has reached or surpassed a critical setpoint, to initiate a corrective action. This action is typically pre-programmed and can range from a simple alarm notification to a complete system shutdown or the activation of a redundant safety system.

Consider a high-pressure boiler in an industrial plant. The system is equipped with pressure sensors constantly feeding data to a control unit. A primary pressure regulator manages the normal operational range. However, integrated within this system is a limit control function, often a separate safety instrumented system (SIS). Its sole job is to monitor for a pressure level that is dangerously high—a point beyond the capability of the primary regulator. If this upper limit is breached, the limit controller does not attempt fine-tuning; it executes a definitive action, such as triggering an emergency relief valve or cutting off the fuel supply entirely. This binary, fail-safe response is crucial for catastrophic risk prevention.

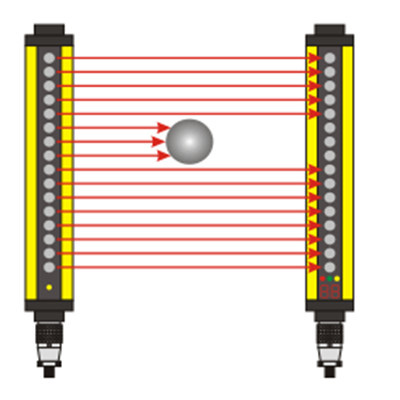

The implementation of limit control has evolved dramatically with technological advancement. Early systems relied on mechanical devices like pressure switches, thermal fuses, or centrifugal governors. These physical devices would actuate at a specific point, providing a robust but often single-use or inflexible solution. The advent of programmable logic controllers (PLCs) and distributed control systems (DCS) revolutionized this field. Now, limit control logic is written into software, allowing for greater flexibility, precision, and integration. Multiple limits can be set—warning limits for operator alerts, high/high limits for automatic corrective actions, and emergency limits for immediate shutdowns. These digital systems also enable sophisticated logging and analysis of limit events, providing invaluable data for predictive maintenance and process optimization.

In the realm of electrical engineering, limit control is equally vital. Battery management systems (BMS) use it to prevent overcharging and over-discharging, which are critical for both performance and safety, especially in lithium-ion batteries. Variable frequency drives (VFDs) controlling motors have built-in current and speed limits to protect the motor from burnout or mechanical damage. In software and network infrastructure, rate limiting controls the flow of requests to a server, preventing overload and denial-of-service attacks, which is a logical application of the same principle.

The design philosophy behind effective limit control hinges on several key principles. First is the principle of independence. Ideally, the limit control system should be separate from the primary regulatory control loop to avoid common-cause failures. This is the basis for safety instrumented systems. Second is the concept of fail-safe design. The system should default to the safest state in case of a failure within the limit control mechanism itself. Third is the careful calibration of setpoints. Limits must be set with a clear understanding of the process dynamics, allowing enough margin between normal operating conditions and the limit to avoid nuisance trips, yet close enough to provide genuine protection. Regular testing and validation are mandatory to ensure the limit controls will function as intended when a real emergency arises.

From everyday appliances like a coffee maker with a thermal cut-off to the complex flight envelope protection systems in modern aircraft that prevent pilots from exceeding structural and aerodynamic limits, limit control is ubiquitous. It represents a fundamental engineering imperative: to design systems that not only perform optimally under normal conditions but also contain their own failures. It is a testament to the foresight embedded in technology, a silent guardian that ensures progress does not outpace safety. As systems become more autonomous and interconnected, the role of intelligent, adaptive limit control will only grow in importance, forming the essential boundaries within which innovation can safely thrive.